The project of posthumanism is to decentre humans as the measure of all things, and as a meaningful interpretive unit for understanding the rest of the world. The emblems of the position they reject are firstly Descartes, as he separates thought from the body (and even gives rise to the thought that the material world and body may well not even exist), and the image of the Vitruvian man which quite literally suggests that 'Man' could be the measure and perfect proportions for understanding the world around us.

In the story of humanism, these moments of the 'rediscovery' of man, are moments of transcendence - where truth, beauty and goodness assert themselves over the base inconstancy of the sublunary world. There is a re-writing of the history before as the 'dark ages' and a diminishment of their cultural value or meaning. Then there is the explosion of knowledge of the Enlightenment.

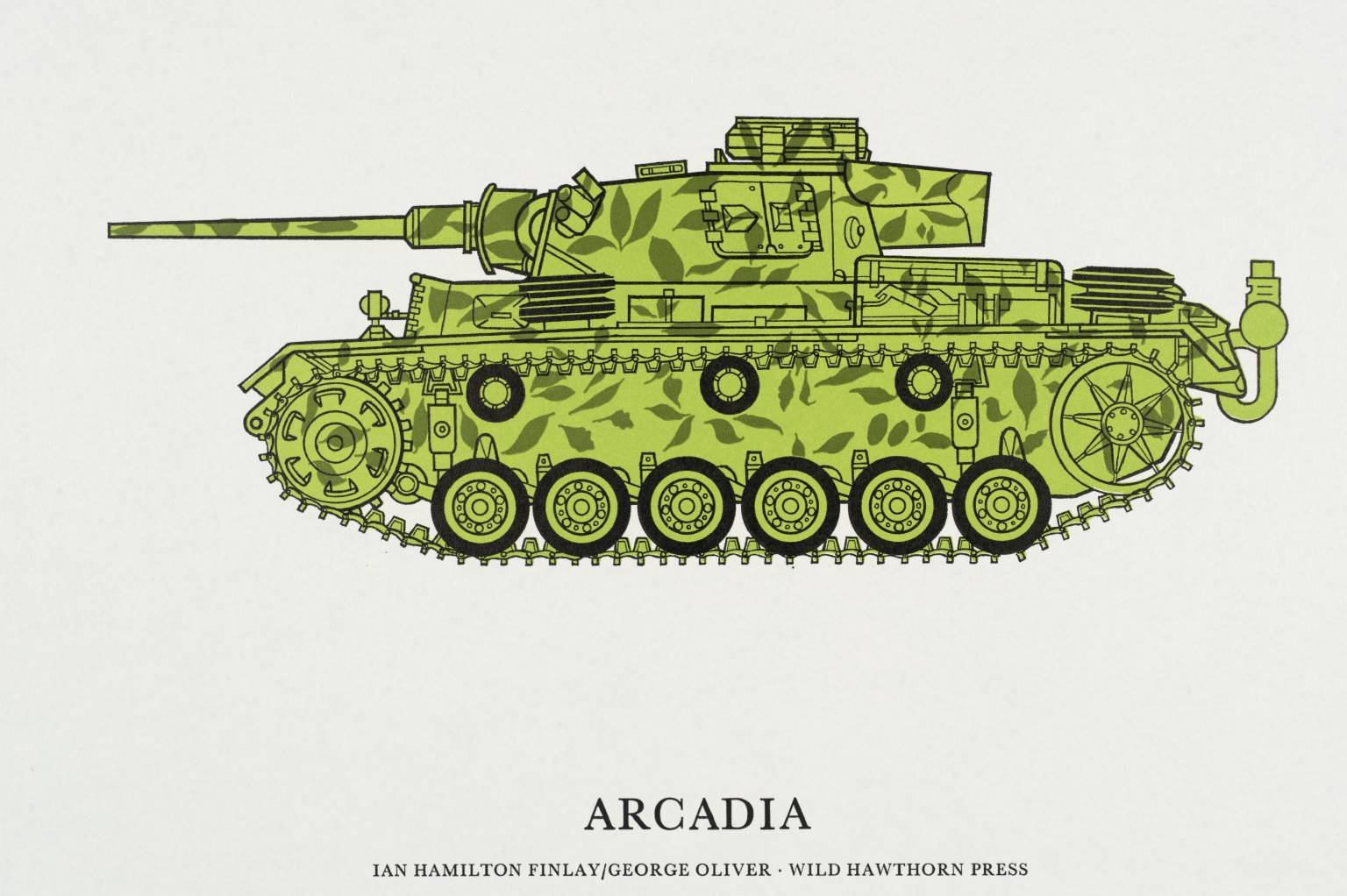

Critics of Humanism and the Enlightenment point of that by centring white, able, European males the movement that gave us the idea of putting human dignity above all, also produced a desire for order and beauty that produced racism, genocide and industrial war in a way that had never been seen before. This is explored by Scotland’s most significant C20th artist Ian Hamilton Finlay, who examines the strange fact that a rage for Arcadian beauty, order and Apollonian calm, generally leads to inhumane violence and intolerance. The image below is a play on Poussin’s picture Et In Arcadia Ego, meaning in paradise is death.

The image below from a work in the Tate, is called the ‘Pipes of Apollo’. The cooling holes of the machine gun, are contrasted to the finger stops on an Arcadian flute played for Apollo the god of order and music in a wood. The series comes from The Third Reich Revisited, a deliberate pun on Brideshead Revisited - a reflection on how nostalgia plays a strong role in extremist pursuits of perfection which end in genocide. This ‘pipe’ was played in the woods during World War II.

Similarly, to the post-structuralists, they noticed that in order to create meaning from the complex, interconnected entanglement of reality, the transcendent approach has a common technique. A verbal definition of identity is formed, then examples and non examples are used to 'split' that which was in fact a genealogically diverse whole, into distinct species. This could be everything from 'civilized and uncivilized' to 'male and female' to 'inside and outside' These binary oppositions form the basis of structuralism that tried to understand them, and post structuralism that tried to point of how contradictory and power laden these dichotomies were. They noticed the way these oppositions and this search for order created everything from social injustice to genocide. Critical post structuralisms abounded for specific groups who worked on a particular set of oppositions - critical feminism, critical post colonialism, queer theory.

Meanwhile in the history of philosophy, a small number of philosophers had been doing something quite different, perhaps deliberately oppositionally, to this way of creating meaning by lifting an element of reality out of the complex whole, splitting it and then using that opposition to create meaning.

Spinoza is perhaps the first in this tradition. Spinoza argues the there is no real value in transcendent meaning. It misses the point that all meaning and 'identity' is in fact immanent within the complex whole of all material. Even God, is not transcendent, but just the fully realised nature of all the material world. Even thoughts are useful only in so far as they full comprehend and match the actual nature of the world around us, and if they do not they are not 'evil' or 'wrong' (which is one half of a binary he wants to avoid making) they are just missing the fullness of reality.

This insistance of positive affirmation, rather than definition by negation in a binary opposition, then resurfaces heavily in Nietzsche's mature works. Deleuze argues Nietzsche is straining for this in his early works, but still relies on binary oppositions like the desire for integration in a whole and the dissolution of self (Dionysus) and transcendent order (Apollo) in the Birth of Tragedy. But in his mature works he rejects the idea of the 'master slave' relationship where identity is formed in a complex entanglement between two people, and instead proposes the superman whose identity is entirely based on positive affirmation and joy. This identity is a complex coming together of elements of the whole, so a particular arrangement of parts, but it seeks nothing but to express itself - just as a particular genetic expression of life is not in 'opposition' to some other imaginary species, but is just an expression of itself.

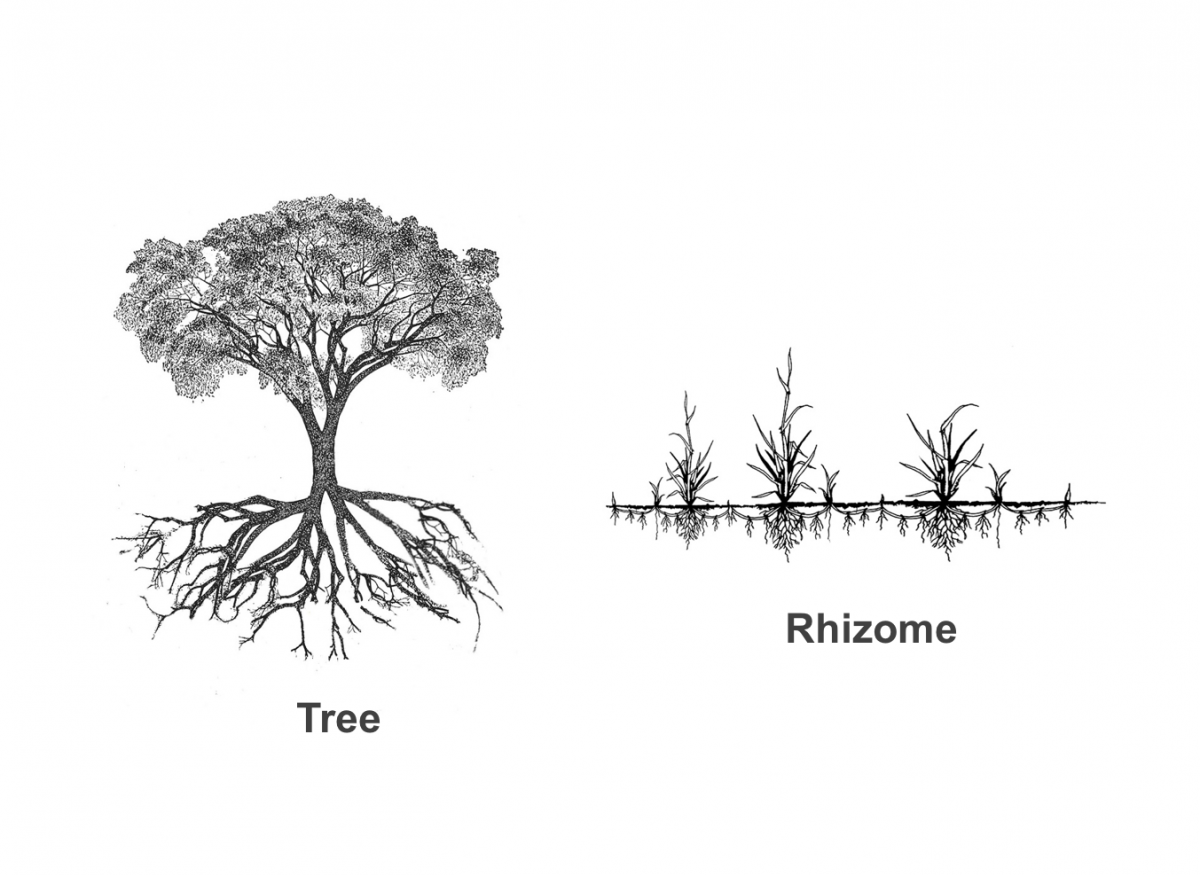

Deleuze takes these two forbears to help construct posthumanism. He reworks the idea of the 'root' or 'tree' as a model of transcendent thoughts, and replaces it with the idea of a complex whole with multiple positive ways of geneaology asserting itself in new complex combinations. Importantly, like Spinoza, the complex forms are no longer limited to thought, or humans; the complex whole is literally everything in the universe - and hence 'vital materialism' is born.

There is meanwhile a parallel evolution happening in Ecohumanism. In Aldo Leopold's The Land Ethic, before even poststructuralism had begun to question the man-nature split, Aldo Leopold suggested that we could extend our notion of 'Kin' not just beyond our family, and not just beyond our immediate allies and friends, but to firstly humanity in general, from there to animals, and from there to the land itself - which we would begin to see have the same rights and status as humans, as we see in examples from New Zealand where rivers and mountains have been given 'human' rights in some contexts. Althought this 'spreading' of rights from the human, is still very much ecohumanism, its end point is the same - and I am curious of the extent to which the use of the word 'kinship' and 'making kin' in Donna Haraway comes from Leopold, who predates her so significantly.

Where does this take us? In one case this takes us to a place where some mud, has the same value as Michelangelo's David - and biologists might argue, rightly so, given the enormous complexity of microbiological life in a small bit of mud. But when we start to suggest that human suffering is entirely indifferent - and just another example of physical matter - we baulk.

Nietzsche and Spinoza already encountered this however - and whilst both deny evil exists, they have a range of arguments about the importance of joy - which resolutely resist a pessimistic reading. It reminds me very strongly indeed of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, where 'every atom belonging to me, as good belongs to you' and he accepts the entire world around him, in its joys and sorrows, with death 'luckier than you thought' - but at the same time, there is no sense of indifference.

Posthumanism takes us to the edge of just such a place Whitman describes and invites us to go inside. So far, it does not describe what you might find there.