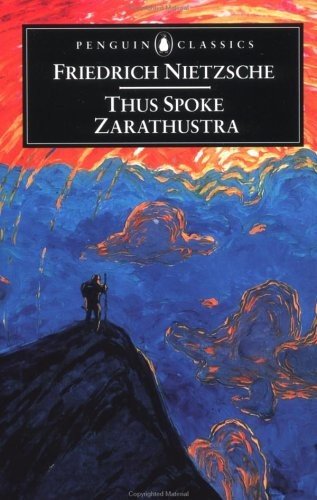

One of the most important moments of my life, was when I realised our time on earth is limited and it was possible to miss out on ‘talking to’ the great minds that had existed before me. I felt a sudden urgency to make sure I had read their words before my time was up. My first thought was Plato, and as a 14 year old I rushed out to the bookshop to buy and start reading as much and as widely as I could. Then it started:….moral philosophy, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Kant, Freud, Jung, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Cervantes, Eliot, Kierkegaard, Woolf, Hesse an endless stream of authors and thinkers followed in rapid succession.

I literally grew up in progressive schools, with parents as school leaders and teachers. My earliest memories are all in schools - either our boarding house home, or sitting in my mother’s class as a toddler listening to her teach. One day I found a book of my mother’s about Coleridge’s vision of education. What struck a chord for me was an idealised vision of childhood and getting knowledge of the Platonic forms that lend divinity to all that is around us. This is what I came to know as the humanist tradition. Plato, Erasmus, Rousseau, Kurt Hahn, Patrick Geddes, and Pestalozzi’s ‘hand heart head’ which had been used by the founder of the school I lived in, John Haden Badley at Bedales. In an idyllic setting, where beauty and the promise of eternal bliss seemed to be hanging in the air between oak trees and hazel coppices, and in the incredible suspended, pregnant stillness of the library, it seemed as if heaven were nearly ready to reach down and touch the earth and bring revelation - and if we just watched carefully, flashes of this perfection of ‘truth, beauty and goodness’ would flash before us euphorically.

Bedales Library

But that was then. And now I think differently.

Humanist transcendental thinking assumes that the world ‘makes sense’ in a way that is detached from the very material world we live in. Plato thought our world was just made up of shadows of the actual ‘real’ world of ideas. This transcendental view runs through almost all Western thought and the Christianity that helped define it before the Enlightenment. It sounds benign, until you understand that systematic devaluing of the real complexity of the world we live in, also gives licence to treat that world as a means to an end, which lies beyond this world or the critters in it.

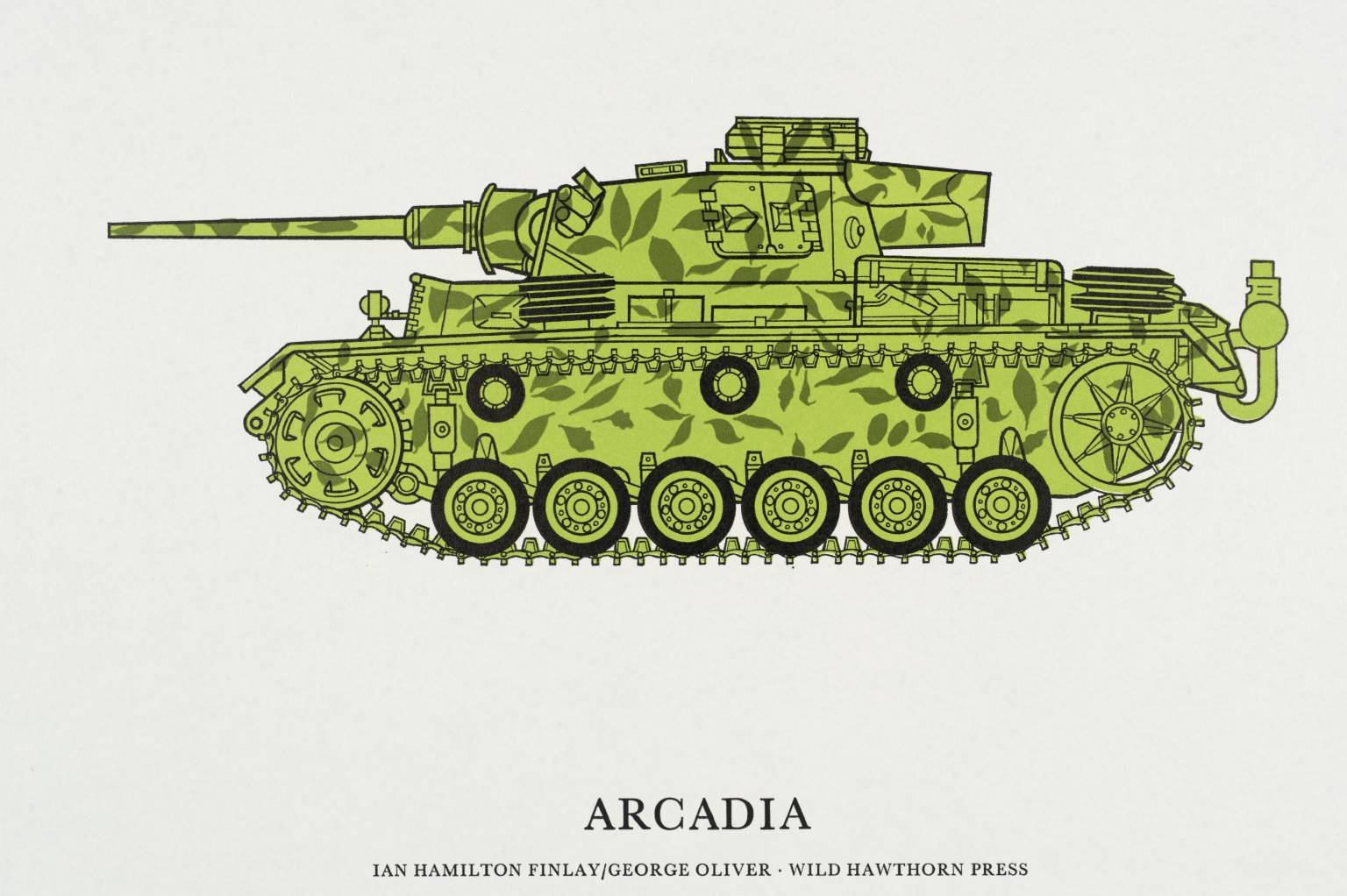

In pursuing an abstract order we created science (which I would argue is a good thing) but we also invented a relentlessly extractive economy, practices which not only dehumanise people by separating us from vivid connections to the rich material world we actually live in, but also the 6th mass extinction the planet has witnessed and catastrophic loss of biodiversity, not to mention climate change. It also allowed the logic that created colonisation and the imposition of ‘order’ upon the world as an act of violence - as after all, it was the ideal of order that mattered the most. It is not far from the ‘chain of being’ to the arguments in favour of racist slavery and colonial violence. Not very far to the opinion that imposing order in the form of ‘civilization’ and ‘education’ was a benign end of colonisation. Nor very far to the violence done to almost every group that was not rich, male and white. From children, to woman, to animals, to the neurodivergent, to disenfranchised workers etc. etc. all have a relentless history of violence and abuse at the hands of a philosophy that on the surface promised ‘truth, beauty and goodness’. The challenging thing is that those dreams, still sing to us like sirens from the sea.

Curriculum and the desire to impose an abstract order on learning was a bed fellow of industrialisation and colonisation. They belong together and helped create each other. Reading curriculum documents and learning goals, used to bring me humanist joy in the perfectability of human kind and the light of learning - but now reminds me of Heart of Darkness: a moment where we realise what has been celebrated as light bringing, suddenly becomes a site of violence and control over a world that was doing quite well without it, thank you very much. Edward Said in Orientalism points out what France did when it invaded Egypt was produce huge maps and accounts of it to force and impose an imperial order upon a rich living ecosystem - it was an act of violence and control in the guise of erudition and learning. The desire to control learning, rank, select and control children is not so very different - and we turn a blind eye to the children who are routinely failed by our systems, despite it hiding in plain sight all around us.

Even the work I have done on competency based learning and learner profiles I now question. It feels like the relentless logic of capitalism to move into a area (like character), re-domain and map it, and then sell back the improvised framework to those who have just been dispossessed of their authentic and contextualised reality. It reminds me of the way supermarkets destroy local fish mongers, and then sell back a sanitised and standardised ‘fish counter’ in their stores which reminds you of the local fish shop that used to exist, but has now been fully tamed and domesticated and has no local fish in it.

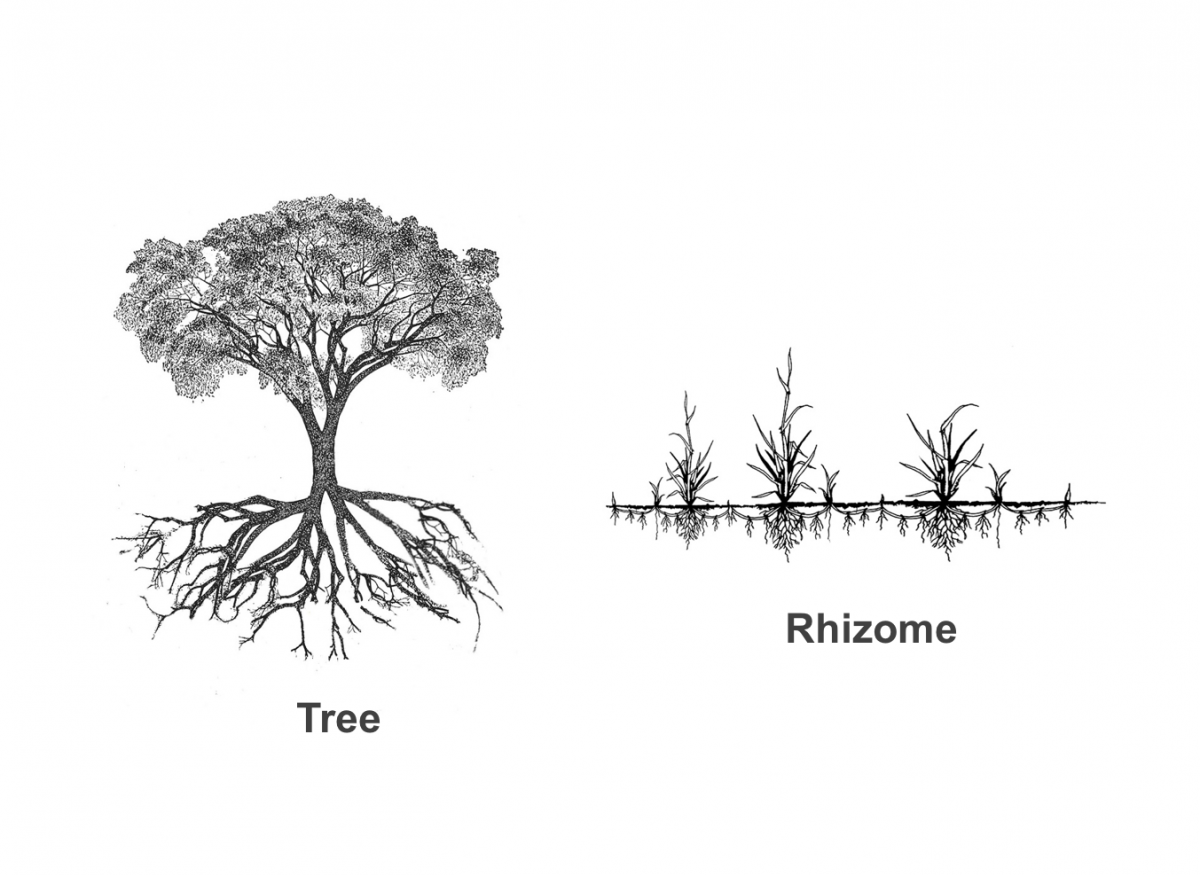

As we move from the industrial to the regenerative model of society and education, what interests me now is reconceptualising how we think about frameworks and ideas.

What if…

What if we realised that learning, ideas, concepts or thoughts (if I use these interchangeably) are like species - they intermingle their DNA with the people they interact with. They spread and interbreed. They thrive or dwindle. They interact with a material environment that is real and richly complex. They are always embodied and situated. Learning is not a platonic abstraction - rather learnings have a rich genealogy that is profoundly entangled with real things, and real people. Ideas, thoughts and learnings can live and die well alongside us in a complex ecosystem of human, non human and more than human beings and kin. What if rather than constantly seeking to impose an invasive species, much as white settlers did in countries like New Zealand which inflict violence upon what is already there, we sought to understand our rich, entangled ecosystems. What if rather than dreaming of a perfectly orderly future we learned to ‘stay with the trouble’ of the extraordinary, chaotic and strange world we actually belong in and to. What if we saw top down curriculum as an invasive species crowding out what is already there?

We often hear of the ‘policy practice gap’ and the problems with implementation. What if what we heard when we heard that was ‘we tried to inflict a transcendental order upon a world that rejected and resisted the violence of that act, because it could not become entangled and a part of the rich human, more than human and other than human lives if sought to change from the outside. It came as conqueror not kin?’

There is a model of curriculum that sits within the top down implementation of policy and ‘best practices’ . I believe its time is passing.

I see practices, some older like Reggio Emilia early childhood education, or some more recent, like the aspirations and work of Education Scotland, that begins to show us a way forward. Curriculum as an invitation to notice, listen, become attuned, co-construct and leave us open to possibilities - which will be made and shaped by the rich entangled places they happen in. That resists the urge to dominate from the centre, but instead entangle with the embodied complexity of what already is.

I have perhaps overstated my resistance to the imposition of order through frameworks to make my reservations and sense of need for new insights clearer. In that light, I would simply state that the poet that gave us ‘truth beauty and goodness’ also gave us ‘negative capability’. Perhaps in that fertile tension the future of education lies. But I am done with transcendent curriculum models and frameworks. At North By Northeast, in August 2025, we will begin to embrace other nuances and ways of making sense of learning.